Gems from the Collaboration Archive

Living Laboratories of the Life Divine

DEBASHISH BANERJI

This is a transcript of a talk given by Dr. Debashish Banerji at the 2003 AUM Integral Yoga conference in Los Angeles.

Commentaries on this article are available on YouTube:

- “Evolving Human Consciousness and Post-Humanism” with Debashish Banerji

- “Nietzsche’s Superman + Sri Aurobindo’s Supermind (Human Consciousness Evolutionary Theories),” a roundtable discussion

- Discussion highlights (short excerpts of the above two video, broken down by topic)

Today I will speak on the subject “Living Laboratories of the Life Divine.” By “living laboratories” I am referring, of course, to Sri Aurobindo’s justly famous phrase taken from The Life Divine. But before turning our attention to that phrase, I would like to back up a little in time and consider the idea of the superman as it makes its beginning in the utterance of Friedrich Nietzsche.

In many ways, Nietzsche, as a philosopher, can be said to inaugurate the modern age. Modern philosophy, where it has been fruitful, has been largely an engagement with Nietzsche’s thought. Nietzsche is a controversial figure, a very complex figure. Complex, because he received intuitions from above and uttered them in a new kind of way that challenged the metaphysical tradition. He also introduced ideas—new ideas—that were half-baked. Often, they were not well-formed, and sometimes they were inconsistent. So to denigrate him or to adulate him is, in either case, a dangerous thing.

Nietzsche introduced the idea of the superman in his work Thus Spake Zarathustra. I will read out a passage from this work. In recent translations of this work, the German term Übermensch has been rendered as “overman” instead of “superman.” Some of us are familiar with a similar kind of replacement that has been attempted by Georges Van Vrekhem, who has translated the Mother’s surhomme as “overman” rather than “superman.” I do not wish to enter into technical controversies or debates over these terms but bring to your notice that there is a degree of fluidity about these things that lend themselves to varieties of interpretation.

I read you Walter Kaufmann’s translation of Nietzsche’s passage:

I teach you the Overman. Man is something that shall be overcome. What have you done to overcome him?

All beings so far have created something beyond themselves. And do you want to be the ebb of this great flood and even go back to the beasts rather than overcome man? What is the ape to man? A laughing stock or a painful embarrassment. And man shall be just that for the Overman. A laughing stock or a painful embarrassment. You have made your way from the worm to man and much in you is still worm. Once you were apes, and even now, too, man is more ape than any ape.

Whoever is the wisest among you is also a mere conflict and cross between plant and ghost. But do I bid you to become ghosts or plants?

Behold, I teach you the Overman. The Overman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say: the Overman shall be the meaning of the earth! I beseech you, my brothers, remain faithful to the earth and do not believe those who speak to you of other-worldly hopes! Poison-mixers are they, whether they know it or not. Despisers of life are they, decaying and poisoned themselves, of whom the earth is weary: so let them go …

Verily, a polluted stream is man. One must be a sea to be able to receive a polluted stream without becoming unclean. Behold, I teach you the Overman: he is this sea; in him, your great contempt can go under.

What is the greatest experience you can have? It is the hour of the great contempt. The hour in which your happiness, too, arouses your disgust, and even your reason and your virtue …

Man is a rope, tied between beast and Overman—a rope over an abyss. A dangerous across, a dangerous on-the-way, a dangerous looking-back, a dangerous shuddering and stopping.

What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end: what can be loved in man is that he is an overture and a going under.

I love those who do not know how to live, except by going under, for they are those who cross over.

I love the great despisers because they are the great reverers and arrows of longing for the other shore.

I love those who do not first seek behind the stars for a reason to go under and be a sacrifice, but who sacrifice themselves for the earth, that the earth may someday become the Overman’s …

I love him who does not hold back one drop of spirit for himself but wants to be entirely the spirit of his virtue: thus he strides over the bridge as spirit.1

It is a very interesting passage, a profound passage, a passage that I wanted to read out because many who have read Sri Aurobindo have never read Nietzsche, and have acquired certain preconceptions of what the Nietzschean superman is all about. I would encourage them to divest themselves of these ideas. Nietzsche inaugurates the future destiny of the human race in the modern age; at a crisis point in western civilization, he holds out the goal of the self-exceeding of man in the superman. We don’t need to assume that Nietzsche himself knew with clarity what he meant by the term “superman,” but it is best to receive the complexity of his thought and see its vastness and its greatness. We should look at it side by side with the superman as envisaged by Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, and at how their superman relates, if at all, to Nietzsche’s idea.

I read first from the Mother a familiar passage. It is from a talk to the children of the Ashram:

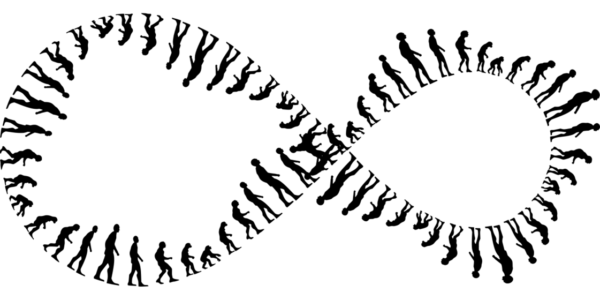

There is an ascending evolution in nature which goes from the stone to the plant, from the plant to the animal, from the animal to man. Because man is, for the moment, the last rung on the summit of the ascending evolution, he considers himself as the final stage in this ascension and believes there can be nothing on earth superior to him. In that he is mistaken. In his physical nature he is yet almost wholly an animal, a thinking and speaking animal, but still an animal in his material habits and instincts. Undoubtedly, nature cannot be satisfied with such an imperfect result; she endeavors to bring out a being who will be to man what man is to the animal, a being who will remain a man in its external form, and yet whose consciousness will rise far above the mental and its slavery to ignorance.

Sri Aurobindo came upon earth to teach this truth to man. He told them that man is only a transitional being living in a mental consciousness, but with the possibility of acquiring a new consciousness, the Truth-consciousness, and capable of living a life perfectly harmonious, good and beautiful, happy and fully conscious. During the whole of his life upon earth, Sri Aurobindo gave all his time to establish in himself this consciousness he called supramental, and to help those gathered around him to realise it.2

There is much in this that bears resemblance with Nietzsche’s description of the superman. Both texts are explicit about the transitional character of the human species. The Mother’s statement actually contains within it Sri Aurobindo’s famous assertion, “Man is a transitional being”—and for Nietzsche, “Man is a rope tied between beast and overman,” and again, “Man is a bridge and not an end … ” Secondly, both texts emphasize an earthly destiny. And finally, note the not-so-noble appraisal of the human being. Man is no longer the “measure of all things” extolled in the European Renaissance, the source of Western civilization’s hubris. While the human being in the Mother’s formulation may not be the contemptible worm of Nietzsche, it isn’t too far from that either. The Mother quickly disabuses humanity of its exalted notion of itself.

I now read Sri Aurobindo’s passage from The Life Divine where he likens us to “living laboratories”:

The animal is a living laboratory in which Nature has, it is said, worked out man. Man himself may be a thinking and living laboratory in whom and with whose conscious co-operation she wills to work out the superman, the god. Or shall we not say, rather, to manifest God? For if evolution is the progressive manifestation by Nature of that which slept or worked in her, involved, it is also the overt realisation of that which he secretly is.3

Let us ponder these three texts. In all three, there is the notion of the self-exceeding of man. The human being has to exceed himself, because from the viewpoint of the imperfection of nature, humanity is as faulted as the animal, the worm is to the human being. It is to set our sights on that kind of goal that Nietzsche is calling us through the voice of Zarathustra. But Nietzsche’s call is going out to the will of man. It is not a simple call to the ego—it is not a call to titanism as has been popularly supposed. It is a call to sacrifice, to vastness. It is a call to the formation of the gods within us.

The overman, according to Nietzsche, is like the gods of the Greek classical heritage. It is Nietzsche’s allergy toward the Christian tradition that makes him deny God. But it is in the becoming of God or of the gods in human guise, that his message lies. But it ends there. What apart from the human will is there to lead us to this goal? If we are hardly more evolved than the worm or the animal in most of our nature, what hope do we have, except for willing something that is faulted into existence in our drive upward?

The animal is a living laboratory in which Nature has, it is said, worked out man. Man himself may be a thinking and living laboratory in whom and with whose conscious co-operation she wills to work out the superman, the god.

— Sri Aurobindo

If we look at Sri Aurobindo’s and the Mother’s texts, we see one critical element that is missed by Nietzsche. They are not talking about the human will attaining to the superman. They are talking about the human being as the site where the superman is formed by agents other than the human. In both cases they use the term nature to indicate this extra-human agency. What is it that they mean by nature? Evidently, if there is something that ties these uses of the word to some common ground, we have to think of nature as the evolutionary force in a conscious form, the evolutionary will.

Sri Aurobindo’s texts need to be read in a cross-cultural context. They have contexts that are equally Eastern and Western. Nature, in Sri Aurobindo’s usage, carries in its background the entire metaphysical Romantic tradition, the European tradition of nature as a cosmic presence and power. With the metaphysical “death of God” and the birth of the modern age at the turn of the 18th to the 19th century in Europe, German Romanticism found nature as a replacement for God—nature as a power with an intelligence instinct in it, as a cosmic container, a Mother-Force. It is in this sense that the English Romantic poets also extol nature. Sri Aurobindo draws partly on this tradition in his usage.

But for Sri Aurobindo, nature is equally and perhaps even more so all that that term means in the Indian tradition when it is translated as prakriti. Sri Aurobindo has written extensively about this term, the various things it means and has meant. The term comes to us from Sankhya4 as that mukhya, that “chief” of the manifest world that is the primary force manifesting things. It is that which drives us, drives everything—matter, life, and mind. It gives us the sense of agency through the creation of an ego, ahamkara, but actually is the complete authority through the operation of its three gunas—sattwa, rajas, and tamas5—of all that happens in us.

But prakriti, from an even earlier tradition, lost and then revived in the Gita, has two faces to it. It returns to us in another guise through the Tantra in two colors, dark and golden, which occupy two hemispheres and two different modalities, para and apara. Apara prakriti is of the lower hemisphere, of avidya, ignorance, wearing the dark guise of unconscious nature, the automatisms of Sankhya. It contains the laws that are coded into matter, life, and mind that run everything, within which we are given the illusion of consciousness. Para prakriti is the unveiled force, Nature‐Force of the Supreme Divine. It is the calling forth into becoming of Being, of the One Being, the only Being there is.

This dichotomy, this two-fold nature, is contained and encapsulated in that simple word nature that Sri Aurobindo and the Mother use in their texts. Because, indeed, the way to the superman, as far as Sri Aurobindo is concerned, is in these two hands of nature, both of these aspects of nature. The lower nature, ignorant, is still instinct with the force of divinity. It has moved matter into the domain of life. It has moved life into the domain of mind. It will move mind into the domain of supermind.

But the question is, when? Nature has eternity in her hands, as the Mother has said. Nature doesn’t care for our time schemes. Nature experiments, plays with forms, possibilities, and ideas, and creates this plethora of manifest realities that we find so delightful in this world. We build our botanical gardens and our zoos so that we can travel through these parks and delight in these multitudinous and wonderful creations of nature. Nature has thrown up our human diversity too, our diversity of types, our diversity of thinking, our diversity of cultures. It is all the doing of nature, and she is here to play in infinite more games, because she is the creative spirit. Progress takes place at her own slow pace through all this.

But the human being, as Aswapathy expresses to the Supreme Mother in Sri Aurobindo’s Savitri,6 is a hapless unfinished experiment of nature. It is a product of nature’s half-finished march toward super-humanity, caught between the worm and the God. From life to life, we suffer the pains and discords of a half-baked consciousness that yearns to exceed itself, that is replete with complex problems it can never solve because of a fundamental incapacity. It feels trapped and imprisoned and cries out for moksha, liberation, ultimate escape out of this prison‐house of the round of suffering and insoluble complexity, finding no other goal.

This is where Sri Aurobindo intervenes to indicate that nature has another poise—the poise of nature in the knowledge, in the vidya. This higher nature is the golden Mahakali behind the black Kali, the body of light, of knowledge, of gnosis, the gnostic Mother. And it is this gnostic Mother, when she descends, who becomes active as the unveiled power controlling the lower nature, who can change everything within the avidya, who can change the conditions of the avidya. For then, it will be no longer a play of trial and error, a slow and painful growth through eternity of the ascending powers of consciousness, but of the future bringing the present into itself, a precipitation of the goal that begins working within the present, transforming it to its own conditions.

This is the one reason why Sri Aurobindo chose to spend all his time and all of his superhuman yogic power to focus on the bringing down of the supermind. He could very easily have sat in his room in Pondicherry and accomplished what he has said some yogis have done in the Himalayas—brought about revolutions in the world. Not only could, he did—a number of them—but he wasn’t satisfied with that, because it could not solve mankind’s problems.

The problems of humanity cannot be solved by a change of the external conditions, or even a temporary change in the inner consciousness of individuals or peoples that causes them to do exalted things beyond their habitual or normal capacity.

The problems of humanity cannot be solved by a change of the external conditions, or even a temporary change in the inner consciousness of individuals or peoples that causes them to do exalted things beyond their habitual or normal capacity. For an hour God resides in a nation or in a time. We experience an hour of God. Human beings are empowered temporarily to do deeds they never could have done; but then, as in the first canto of Savitri, “The Symbol Dawn,” inevitably the power recedes, and we are left to “the common light of earthly day.” We are back to business as usual, the sordid poverty of human life.

There is only one way that this can change. It is not through our unaided effort, but through the bringing down of a force, which in spite of us, can change conditions here. But the “in spite of us” has to be understood in its right dimensions. This change of conditions is not an external or a temporary change, it is first and foremost a radical change of consciousness—and this cannot occur without our conscious cooperation. As Sri Aurobindo puts it in the statement I have quoted from The Life Divine, as always, with every aspect of the question included, “Man himself may well be a thinking and living laboratory in whom and with whose conscious cooperation she wills to work out the superman, the god.”

Let us make no mistakes about the priorities of this process. It is the para prakriti, the supreme or higher nature, who is the scientist of this laboratory. It is we who serve her purpose through our adherence. We are the conscious cooperators. Sri Aurobindo and the Mother’s primary yogic work has been to change the agency of this process from the lower to the higher nature, or rather, to establish the higher within the lower. And what is called the supramental descent and manifestation is exactly the collapse of the division between the vidya and the avidya. It is the implosion of the knowledge, the power, the vijnana-shakti into earth, and that entry has initiated a new age.

A new age does not start by astrological factors. It is not because it is written in the calendar that a new age suddenly begins. A new age is an act of consciousness. It is a powerful act of consciousness, willed by the human cooperators and assented to by the Divine.

A new age does not start by astrological factors. It is not because it is written in the calendar that a new age suddenly begins. A new age is an act of consciousness. It is a powerful act of consciousness, willed by the human cooperators and assented to by the Divine. And this is the new age that Sri Aurobindo and the Mother have inaugurated. It is a new age, first and foremost, of world yoga. It is a new age of yoga and of world-yoga—yoga, the accelerated process toward conscious evolution. Prakriti, nature, has always been doing yoga. This is why in The Synthesis of Yoga Sri Aurobindo can say: “All life is Yoga.”

But the yoga of nature is a slow, semi-conscious process. The yoga of human beings who wake up from within by the pointing conscious finger of light that comes as a beacon showing the way is a conscious yoga. It is a conscious yoga that accelerates and quickens the process. It condenses into a lifetime or a few years what would otherwise have taken many lifetimes. It brings the future into the present. This is exactly what Mother and Sri Aurobindo have done on a cosmic or terrestrial level. They have initiated the earth into a new yoga. The ear of the earth has been privy to the mantra of a new yoga and has accepted it. That yoga has begun.

Conscious yoga condenses into a lifetime or a few years what would otherwise have taken many lifetimes. It brings the future into the present.

We heard in a talk yesterday about the conditions of the earth and about the earth as the ashram, the ashram of the world. Ron Jorgensen spoke of the entire world as the home of the Lord, and of the circumstances that come to us in the world as being provided by the Lord for our yoga. Indeed, it is the ashram of the world that all humanity can be said to inhabit today, and in a profounder sense than of providing materials for the growth of consciousness in those who have chosen to take up yoga. It is the ashram of the world because the world itself has been moved into a world-yoga. This is the meaning of the new age.

I would like to draw your attention at this point to an ancient story, a story from the Puranas, a story that tells about an occult event that happened in eternal time, an eternal event. It is a story about a great churning of the cosmic ocean so that the pot of amrita, the ambrosia of immortality that is at the bottom of the ocean, will be brought to the surface, will be churned up from the bottom. The gods and the demons together undertake this churning. The great world mountain, Mount Meru—which also is in each of us as the merudanda, the spine—the world axis, axis mundi, the pillar of the world, that is used as the churning rod. The great serpent Ananta—who is the base of the evolutionary fountain of avatarhood, of Vishnu—the coiled infinite potential of Time, with Eternity on one side and Perpetuity on the other, eternally changing, never changing, is used as the churning rope. And Vishnu himself, as the tortoise avatar, is the base on which the churning rod, Meru, is stationed.

The first thing that happens with the churning is the rise of the poisons of the ocean. The poisons of the ocean are so dense, so acrid, so corrosive, that even the demons cannot continue. Both the gods and the demons are completely stalled. The sky turns black with poison. What we today call pollution is as nothing compared to that condition. Man cannot even envisage that condition of poisonous darkness. Neither the gods nor the demons can cope with it. It is at this point that the great Lord Shiva himself comes to the rescue by drinking the poison and holding it, by his yoga-power, in his throat, which is therefore stained blue. This is why Shiva has as one of his names, Nilakanta, the blue-throated.

A number of mystics had experiences around the 5th of December, 1950, at the time when Sri Aurobindo left his body, and several of them saw a vision of the great Shiva drinking the cup of poison. Indeed, the departure of Sri Aurobindo can be understood in this light. The myth of the churning of the ocean is an image of the world yoga initiated by Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. Sri Aurobindo has prepared the process, he has initiated it and he has sacrificed himself so that our unprepared nature may be able to bear the intense difficulties of the beginning.

It is the first stage of this world yoga that he has made possible by drinking the acrid poison that rose up from the depths. He has held the supramental light in his body and he has broken the backbone of earthly karma, which would have otherwise made it impossible for us to move into this new age. This is why the Mother has addressed Sri Aurobindo’s “material envelope” and said, “Before Thee who has willed all, attempted all, prepared, achieved all for us, before Thee we bow down and implore that we may never forget, even for a moment, all we owe to Thee.”7

The pollution that we see is inevitable. It is the result of our collective consciousness. It is the poison-fruit of our world karma facing us as we take our first steps in the new age. It is necessary. It will pass.

All that we see and experience today are the physical repercussions of occult events of this kind. The pollution that we see is inevitable. It is the result of our collective consciousness. It is the poison-fruit of our world karma facing us as we take our first steps in the new age. It is necessary. It will pass. It has already been dealt with by the Lord himself.

But this world yoga, though much quicker than the processes of nature, is still a process of collective preparation that is impersonal and relatively slow, because it is a process of bringing consciousness to the unconsciousness. It is awakening it, but awakening it over time, slowly. People receive ideas. In a talk yesterday we heard a whole spate of names of people who appear to be doing the work of the Mother without knowing that they are her instruments. Indeed, they are, and yet the purpose has not yet become conscious in them, the fullness of divine intent has not dawned on them. They are serving the world yoga.

The work of the supramental consciousness occurs not merely at the universal level of the world yoga, but also at the individual level and at several other levels. It is conducting many experiments simultaneously and in an interrelated fashion too complex for the human mind to comprehend. As Sri Aurobindo says in the book The Mother, the Mother’s steps are very complex, “one and yet so many-sided that to follow her movement is impossible even for the quickest mind and for the freest and most vast intelligence.”8

This is why surrender is demanded of us. It is only through surrender that we can progressively become more enlightened instruments of her workings, and in the process find ourselves more and more a part of her. By this means, we are to rise to a consciousness one with her consciousness, a state from which our present condition will seem indeed very embarrassing. In this progression of the world yoga, we have to be open to the vast, complex, global, and minute working of her supramental shakti, that reality which is here among us. The living laboratory is not just the individual, nor is it merely the work to ameliorate world conditions, it is these and a variety of other experiments that are going on at the same time.

When Sri Aurobindo and the Mother were in Pondicherry, the Mother has said that there was a question whether they would do the yoga with just a handful of disciples, to intensely try to accelerate the process of the descent of the supermind, bring it down and then radiate it. She said the other option was to go slower, but to gather around them representative specimens of humanity that would be able to bring a much wider possibility of the manifestation of supramental consciousness on earth. She says the decision was not made mentally. The Lord made the decision. It happened by itself—and it is the second course that was followed. This was how the Sri Aurobindo Ashram developed.

We who have been touched by the message of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother have taken maybe a few faltering steps in the direction of the light that they have shown, the goal they have shown, have inevitably felt at some point how privileged we are, how fortunate we are. What a grace we have received. Let us not be fooled that it is due to any credit of ours that we have been chosen for this grace. It is a process that has selected us.

The phrase “living laboratories” is very relevant here. We are “cultures” both in the sense of particular social expressions and in the sense of biological specimens. We are cultures on petri dishes that are being experimented on. We have been chosen because we are representative of something, something which goes far beyond our own understanding. We are here to serve a purpose that will be revealed to us not today, but only when the work is done.

Today or tomorrow, all the earth, every individual, will receive this blessing, because this is the condition of the world yoga. The world yoga progresses through smaller collectives. Not only as the entire body of the earth, but more quickly, much more consciously, through the intention of people who awake to the reality of what the supramental force is bringing.

The growth of the Ashram was around Sri Aurobindo’s and the Mother’s ascension, it was around their attempt to reach the supermind and bring it down for humanity. For that growth, the roots had to extend far into the possibilities of terrestrial manifestation. Diverse specimens of humanity gathered around Mother and Sri Aurobindo at the Ashram—a tremendous diversity. And yet, each individual had personalities that were molded into their highest possibilities by Sri Aurobindo and the Mother—their highest possibilities of manifesting the yoga force.

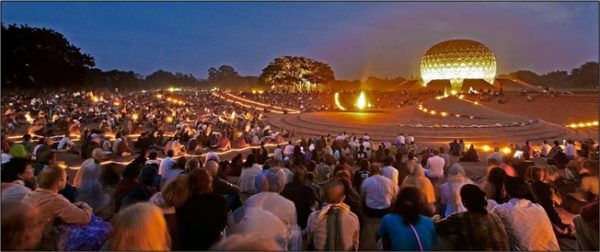

The Mother did not stop with this process. Sri Aurobindo and the Mother had been physically present at the center of the Ashram community as a laboratory of the supramental experiment. But in 1968, she spawned another community with an even wider, more global, planetary basis that would not have them physically at its center. That community would have to open to them internally. Its members would have to be the conscious collaborators in the inner sense, no longer guided externally in the material details of their existence, no longer capable of dragging them down, of pulling at the hem of their robes and soiling them. They also would have to receive the problems of humanity, and they would have to open to the Divine from within and receive the grace of the transformation through collaboration with the para prakriti, with the supreme Mother Force. This is Auroville. Auroville today is continuing in this work. It also is a sphere of churning, a cradle and crucible of the superman.

And yet, this is not all. In a conversation of December 1938, Sri Aurobindo said that a few hundred people in the Ashram would not be sufficient to make the supramental effective for mankind. Thousands of people doing the yoga sadhana in many walks of life across the world would be needed for that. Individually and collectively, across America, across Europe, across Asia, across the world, we are all invited to be participants in the purpose of the supramental manifestation.

The supermind is interested in us. We are not here merely to make conscious efforts, to make titanic efforts, to fling ourselves from this orbit to the higher orbit. We can be heartened by the fact, but we should also be extremely attentive to the fact, that the supermind is interested in us. It is a Force that is seeking us out. It is an agency, an active power. In seeking us out, it is seeking us not merely as individuals, because its purpose is a divine life on earth. A divine life on earth is not manifested by one person.

A divine life is a context, a divine life is an opening up of a world of phenomena that make for a rich collective existence in all its forms. If we cannot provide it with the conditions for this, its work is to that extent hampered or thwarted of the cooperation that it seeks. We need to be conscious of this, because it is only to the extent that we are conscious of this that we can be its collaborators. We need to gravitate together; unite our wills, form collective individualities. We need to form integral collective flames of aspiration that will be able to invoke that higher consciousness and call down that light, that power to work among us, to form itself in us, to radiate through us in our acts, in our bodies. That, indeed, is what it seeks.

The power of the supramental shakti here on earth seeks unity, integration, and perfection. It seeks these in an integral way. We are first called in consciousness to these experiences of integrality. This is the pressure. Can we be integral within? Can we integrate ourselves: integrate our mind, life, and body around the psychic being?9 Can we feel whole, feel one? This is the pressure. The help is coming for this. But again, it is not merely at the individual level. Can we experience the unity of collective consciousness?

In a previous talk we were fortunate in receiving a message which I have heard for the first time—a very refreshing message—that the signs of the supramental manifestation are not to be sought primarily in the breakdown of the Berlin Wall or the fall of Soviet communism, but within us, in the change in the modality of consciousness. Are we aware of this? Let us become aware of it. We live in God. Are we aware of it? It is the consciousness that has to turn within and see what is being done by the supramental shakti inside, not outside. This means an awareness of the process of integration of the being and also its results. We must recognize the fact that unity manifests in and through us when we least expect it. We experience it, but we are not aware of it.

There is a form of experience that the supermind is calling us to have and feel. Individually, great yogis have experienced the Divine, the Oneness, the One Being. And yet, when they have come out of it, they have seen that every individual has remained in the ignorance. Why? Even when they had the experience of oneness, it was only they who had it. When the Mother experienced the descent of the supramental force into the earth at the Ashram playground, it was such a powerful experience she felt that when she opened her eyes she would see everybody flat on the ground. But nobody, except for a handful, even knew what had happened. The ignorance encases us so densely that we are unaware of what is going on within. But the experience, the new spiritual experience to which we are called by the supermind, first in symbolic form, in collectives, and finally as a world phenomenon, is that of collective oneness.

Collective oneness seems at the outset to be a trivial phrase, one of those catchalls of the new age. But it is not that. Collective oneness is arriving at a poise of consciousness above the mind, not individually, but collectively, where a number of people can experience at once that they are the One Being. They look at each other and they know themselves simultaneously as one and yet irreducibly different—a difference because this One Being is not a finite being, it is infinite. The infinite One wonders at its own infinity. It is one and yet infinite. Its own potentialities come to it from its own infinity, and it wonders. This is the content of the experience of collective oneness that the supermind is calling us toward.

The possibility of being is not the only aspect of the supramental invitation. It is also the possibility of becoming, an integral perfection in becoming. For this we must not merely aspire collectively for the supermind to manifest through us, move us as a collective, but we must offer it an integral field, a field of knowledge, a field of work, a field of love and emotion, a field of physical labor and activity.

We offer it an integral field collectively with the consciousness that this is why we are doing this work—not to create an edifice that others will marvel at as some kind of institutional radiation of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother—but to allow the supermind the conditions that it seeks for our cooperation. In the works of knowledge, in education; in the works of will, in business, in politics; in the works of culture, in the emotional life, in the refinement of the senses; in works of the body, of labor, of service, of dasya; let us give all our parts of being fully and collectively, because that is what the supramental force is interested in.

I call upon all of us to meditate on this invitation, because we are called upon to be conscious collaborators, but even more importantly, we are called upon to be living laboratories. We are the living laboratories of the divine life, individually and collectively. To be conscious of this, to hold these possibilities in our being, to be always receptive, this is the call. To have a will for the divine life is good, to surrender the will is better, but to be receptive to the messages of the Scientist who is using us as the site of Her experiment, as a living laboratory, is perhaps the best.

Notes

- The Portable Nietzsche, Kaufmann, W., Penguin Books (1977), pp.124–127

- On Education, Collected Works of the Mother, Vol. 12, p. 116

- The Life Divine, Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, Vol. 21, p. 6

- Sankhya is one of the six classical schools of Indian thought concerned with enumerating and categorizing the principles of existence.

- The gunas are modes or qualities of nature; sattva, rajas, and tamas are the qualities of equilibrium, action, and inertia.

- Savitri, an epic mantric poem closing around 24,000 lines, is Sri Aurobindo’s masterwork.

- Mother had this sentiment inscribed on Sri Aurobindo’s samadhi, the white marble shrine in which his “material envelope” was placed after his passing.

- The Mother with Letters on the Mother, Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, Vol. 32, p. 14.

- The psychic being is Sri Aurobindo’s term for the soul of the individual, the spark of the divine fire that grows behind mind, life, and body and develops in the evolution until it is able to transform the nature from ignorance to knowledge. See Glossary of Terms in Sri Aurobindo’s Writing (Sri Aurobindo Ashram: 1994), p. 119.

DEBASHISH BANERJI was introduced to the writings of Sri Aurobindo in the 1970s following a crisis of meaning pertaining to the technological ontology of our times. He has been a student of Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy ever since—and beginning in 1990 involved equally in academics and Sri Aurobindo community activities in the U.S. He is the Haridas Chaudhuri Professor of Indian Philosophies and Cultures and the Doshi Professor of Asian Art at California Institute of Integral Studies, a founder of the widely read blog Science, Culture, Integral Yoga (2004–2015), and past president of the East-West Cultural Center in Los Angeles (1992–2006). Banerji’s most recent books are the edited volume Integral Yoga Psychology:Metaphysics and Transformation as Taught by Sri Aurobindo and Meditations on the Isha Upanishad: Tracing the Philosophical Vision of Sri Aurobindo.

This article was first published in Collaboration Vol. 29, No. 2 and was reissued in Collaboration, Vol. 45, No. 2/3.

Subscribe to Collaboration

Collaboration explores the vision and work of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, the theory and practice of Integral Yoga, and themes such as consciousness, emergence, and transformation. To subscribe, visit https://www.collaboration.org/journal/subscribe/