On the Lam From the Divine:

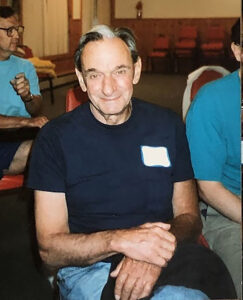

Two Interviews with Eugene ‘Mickey’ Finn

CLIFFORD GIBSON AND JOHN SCHLORHOLTZ

Editor’s note: This piece appeared in the Fall/Winter 1989–1990 issue of Collaboration, vol. 16, nos. 1–2. It starts with an essay by John Schlorholtz recounting the story Mickey told him during an interview at Mickey’s Boston, Massachusetts, apartment and concludes with Clifford’s interview of Mickey.

Mickey summarized it all in this way: “The environment and activity, the total environment around each and every person that that person is conscious of is all organized and structured so perfectly for only one reason: to bring out the hidden truths in life. I’ve never had a vision, I never saw any writing or heard any sounds. It’s just that, little by little, you start to realize that there can’t be any other way.”

The Soldier

Mickey Finn ran away from home when he was 14 years old. He had a good home but found school to be unbearable. He couldn’t keep his mind on simple mathematics, couldn’t read because he was thinking about things outside on the street. After two years of wandering aimlessly around the country, working “for 25 cents an hour” and being arrested in Florida for vagrancy (“They had 32 city ordinances that covered anybody who was broke”), he came back to Boston to volunteer for the Spanish civil war and fight on the loyalist side against the Hitler-backed Franco regime.

Later, although he was too young, he joined the American army in World War II and was sent to the Pacific. After one year he found himself on Guadalcanal fighting the Japanese: “They didn’t have the firepower we had, but they had “knee mortars” that they strapped to their knees when they ran. At night, if they heard a sound anywhere or saw a movement, a whole battery would go off. Eight. There was always eight. You would hear them go off, and the whole eight would be in the air at one time. And you would count them when they landed, and if you counted up to eight you knew you were alive.”

Wounded

At one point he’d been in the rain for five days, saw a grass shack, and went to get out of the rain. The Japanese were there. Mickey heard the explosion, felt himself lifted off the ground, and then down, with his arm wounded by shrapnel. From out of nowhere a Marine picked him up and carried him to safety. He languished in a ill-equipped hospital tent with a severed artery for many days, too weak to be moved, according to the doctors. In terrible pain, but without any painkillers, he convinced an orderly to give him a shot of morphine: “That was the first peace I had felt for three days and nights. And that’s how I got started on drugs.”

The same orderly, a fellow Bostonian named Red, helped smuggle him on a plane bound to another island with a decent hospital. There, a doctor took one look at his arm and said, “Prepare this guy for surgery.” They performed a brand new operation, only recently learned from America’s allies, the Russians, that could join nerve endings that had been severed more than an inch. “I woke up later in the ward,” Mickey said, “and smack! (sound of his fist hitting his palm) I reached over. My arm was there! I coulda done a handstand! I was one of the first soldiers to get this operation.”

The Criminal

After the war he “kinda drifted into a life of crime,” stealing rationed items, like cigarettes, with a gang. He was caught but went on to armed robbery (“After all, the army had taught me how to use a gun!”), safe robberies, and then confidence games at the racetracks. He was into heavy drugs during this time until he tried to sell an ounce of heroin to an FBI agent. “Until I went to jail I don’t think I had ever really read a book. But there I started reading Mickey Spillane and then John Dos Passos. It made me start to think a little bit.”

Once out of prison, though, he returned to crime and drug use, becoming a gifted con man. He was so run-down physically that his friends were taking bets that he wouldn’t make it to the age of 40.

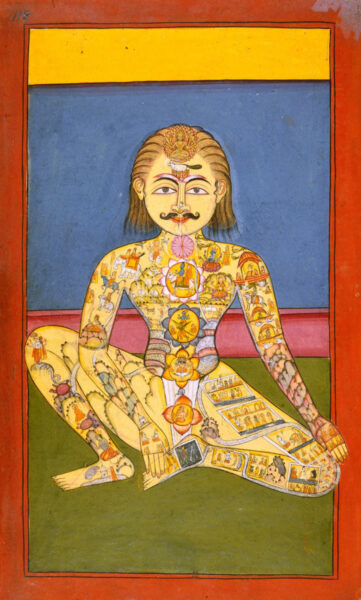

Yoga

One night his wife brought home a book about hatha yoga by Indra Devi. Six months later he picked it up and tried to get into the full lotus position. He succeeded immediately, and his wife later told him that a change had come over him, like he was “transfixed.” So he began to practice hatha yoga faithfully, built himself up, and began looking for more about yoga: “I went to the New York Public Library and stole a book on yoga! I thought that if I developed my mind better I could rob the educated rich!”

But some other part of his being had been touched. One day in Central Park he picked up a newspaper and saw a photo of a woman in a sari, a French woman who called herself Devi. He went over to her “Indian cultural center” immediately. When Devi came into the room he felt electrified. He also wanted to run away, but she offered to see him and talk to him about yoga.

Later Mickey learned that Devi had been told by Ramana Maharshi to go to the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, from where she came to the USA. John Kelly also told him that he had met Devi during World War II when she had been a leader in the French resistance.

The first time Mickey saw her, he remembers her talking mostly about consciousness. “At that time I thought that if you were conscious you were awake and if you were unconscious you were asleep—or knocked out. But I kept going back to see her.”

The FBI and Devi

“Then one day I called my mother’s house in Boston and my mother said, ‘I hope you’re not calling from your house.’ I said, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘Because the FBI just left here, and they probably have our phone tapped.’

I got sick. I was only out of jail 18 months at that time. I really didn’t have any question in my mind as to what it was about. I had just clipped some guy in western Pennsylvania for quite a bit of money. And all I could see was, augh, the walls again. And this time I was really gonna get it because I was already diagnosed as being a psychopathic criminal by the federal government, which means any judge is going to give you the maximum sentence; you’ll never get a parole. Nobody can fix it for you.

“Anyway, I called up my lawyer. I said, ‘Listen, Jerry. I just called Boston. My mother told me that the FBI is looking for me, and they’re waiting outside her door right now. Would you call up the FBI and find out what they have against me?’

“So he did. I called him back; I didn’t even give him my phone number. He said,’Listen, they want you to come in. They got you wrapped up in a package. You don’t have a chance.’ So I said, ‘Listen. Call the FBI back and tell them that I need a week to straighten out my affairs, and then I’ll come in.’ He called them up, and they said they’d give me a week, and they wouldn’t look for me or bother me.

“So, that day I was supposed to go over to see Devi. That afternoon I walked into the room that she used to talk to me in, and she got in front of the door. She put her arms like this [crosses his arms in front of his chest]—I’ll never forget it—she was a very imposing woman. She said, ‘You’re in trouble with the police. Do you want to sit down and tell me about it?’

“I wanted to run out the door. If there was a way to get around her without knocking her over, I would have. Here’s this woman who I’d only met three times, and I had her on such a pedestal that when I had an appointment with her, all day I waited to get there. And how did she know I’m wanted by the police? If they knew about her, they wouldn’t have been at my mother’s house that same day, they would have been sitting outside her place.

“Anyway, she said, ‘You want to sit down?’ —And I said to myself, ‘Boy, there’s no sense lying to this lady. How would she know all this?’ So, I told her … all the arrests and the prison and drug addictions and alcohol and, you know, because that’s where I was at.

“After I got through with this whole story, she never batted an eyelash. She looked at me and she said, ‘Don’t worry about it, nothing’s going to happen to you!'”

“After I got through with this whole story, she never batted an eyelash. She looked at me and she said, ‘Don’t worry about it, nothing’s going to happen to you!’ When I went out the door I said to myself, ‘Boy, is she carried away. Nothing’s going to happen to me!’

“Well, the following week I had another appointment with her in the afternoon. I called up the lawyer, said, ‘Listen, Jerry, call up the FBI and tell them I need another week.’ I wanted to talk to her some more about yoga and Sri Aurobindo—she was always talking about Sri Aurobindo. He called them up and then said to me. They only give you this one more week, and they know they won’t have too much of a problem finding you.’

The following week I called him up and said, ‘Listen, Jerry, they got me wrapped up in a package. What do they want me to come in there for? To tie the ribbon around myself? I’ll come in when they pick me up. Why should I go in and cooperate with them? I’m going to get the limit anyway.’ He said, ‘Okay, if that’s how you feel, I’ll call them up.’ I said, ‘Don’t call them up, just let it go. Tell them you haven’t heard from me.’

Case Closed

“Three months later I called that lawyer up for some other reason completely. He said, ‘I’m going to tell you something strange. The two FBI men that had your case three months ago were in my office this morning. I thought they came looking for you. They never even mentioned you. They came looking for somebody else.’ I said, ‘Well, I hope you didn’t mention me.’ ‘No I didn’t,’ he said.

“I went over to Devi that afternoon, and she asked me, ‘Have you heard anything from your case?’ ‘No,’ I said. She said, ‘Don’t worry about it, I don’t think you ever will.’ And I never heard anything from that case.

“You know, when I first started stealing at the racetrack, it was a pleasure. You know, I thought I was so smart, just talking people out of their money. But, after I got into the Yoga—subconsciously everybody’s in it—but after I got into it consciously it became harder and harder for me to do that, till after about a year and a half it became such a torture to go to the racetrack that I couldn’t do.it anymore. I had cops ask me after that: ‘What was the disposition of this case here in western Pennsylvania?’ I said, ‘Charges were dropped—no evidence,’ but I don’t know what happened. I tortured for years trying to figure out, what did Devi do?

“She didn’t do anything—but I couldn’t understand that. I never told that story to anyone for quite a long time, for years. I figured if I told it to anybody, they’d think I was insane.

“Finally there was a young girl that Wally sent over. She’d been coming to see me for maybe five or six times. she came over to me, and she said, ‘Oh, Mr. Finn, I think there’s something I’d better tell you, but I’m so embarrassed.’ I said, ‘Listen, I’ve been in more holes and sewers than you ever know exist. Whatever it is, if you want to get something off your chest, don’t feel bad telling it to me.’ So she said, ‘Well, I’m out on bail from Florida. I’ve gotta go back in another two weeks to stand trial, and I’m worried about it.’

“She was the first one I ever told that story to. And l told her, ‘Listen, I’m not Devi, so I can’t say nothing will happen to you, but I’ll tell you this: if you stay open to the Light, the Force, the Love of the Mother it will turn out all right, I know it will.’ And she said, ‘Gee thanks, I feel better about it already.’ Do you know she called me up four days later: ‘Mr. Finn, Mr. Finn, guess what happened? All the charges against me are dropped. I’m going to get my bail money back, and that will be the end of it.’ You know, it just worked. It always works.”

Heroin

After that Mickey became an even better thief than before, but it became distasteful, and he kept getting into trouble. He returned to Boston during the early sixties and decided to get a regular job. No one would hire him. He had many doubts about yoga and Sri Aurobindo—kept looking for faults in his books—and couldn’t give up heroin.

Finally he got a job in a foundry, continuing to do hatha yoga, and pranayama [yogic breathing] to get him through the day. He used to think, “That Devi, what did she do this to me for?” He was getting offers from “all over the country” to go back to stealing. He said to himself, “Am I crazy working in here? I can make more money in one day stealing than I can make here working in three months. I must be out of my mind. I might work in this foundry for a hundred years and never find out if this is all really true. Maybe Sri Aurobindo’s just such a brilliant writer, and maybe he could write all these things without any flaws and make a perfect plan of what existence might be like. But it might not really be like that. It’s his way of seeing it, and maybe it’s not all true.”

And then he’d say to himself, “But if I go back stealing, if what he says is really true I’ll never find out. But supposing I work here for 50 years and never find out? Why don’t I get a sign or something to show me it’s all real?

“You get signs every moment of your life, but you can’t see them because they’re too subtle. I worked in that place for eight months. Finally I found out that you inhale the metals and everything through your pores, through your breathing—it gets on your food when you eat. The inspector came around to find out if my urine was alright, so I asked him, ‘What is all this about?’ ‘When it reaches the danger point,’ he said, ‘we tell them to lay you off.’

“I was looking for an excuse to get out of there anyway—it was a torture chamber. So I quit I went to a cooking school. The state was paying the freight and paying your living expenses. And I checked into a motel out on Route One and, oh … I got up the first morning—wall to wall rug. I didn’t even have a radio or a television where I lived before because I was making such small money, I was working for minimum wage. I jumped in the shower, and I’m toweling myself and, you know, it felt so wonderful with the music going, and I was floating around the room. Then I looked in the mirror—the first time I saw myself in the mirror in eight months—I couldn’t believe the change that had come over my body. Pheew! I was not in good shape when I went to work in that foundry. l’d just come off of drugs. And here I was solid again. Then I opened up the book, The Mother, where it says that in each man she handles and answers the needs according to the force that is in him and the consciousness that it’s done in—and I said, “My god, I needed to get built up and she threw me in the foundry and gave me a body again.

“I was still using drugs, but not so heavy. But every time I would take a fix, after I took it, I would say—ah … ‘Sri Aurobindo is brilliant, Devi was brilliant; what do they know about junkies? From what I read in these books, you have to always be concentrated on the Yoga, on the Mother. I can’t even go for ten minutes without thinking about a fix.’

“This went on for a long time. Finally one day, I said it before I took the fix, I said, ‘Well … I’m not going.’ It was raining out. I was supposed to meet the connection on the street corner, I said, ‘I’m not going. I’m crazy, because I’ll be looking for that guy tomorrow morning and he’s going to be mad as a son-of-a-gun, that I left him standing in the rain and, ah, I’ll be sick all night.’ And I didn’t go.

“You know, I didn’t think of drugs for two weeks, and then it came to my mind that I hadn’t been bothered for two weeks by this … thing that I was hooked into for all these years. You know, it’s awful hard to pass that by and say … you know, the foundry was easy, but drug addicts, when they stop using drugs, they get sick as … oh, they get so sick. I didn’t have a bad minute. So, I opened The Mother again [laughs]. Mahakali: In one moment she breaks things without consistence, the obstacles that immobilize and the enemies that assail the seeker. Drugs went like that—she snapped it like it was a straw.

“I couldn’t believe it, except then I started to think back about Devi with the police looking for me and I said, ‘My god! This is the most beautiful thing that could ever happen to anybody.’ You know what I mean? And the next thing, all of a sudden I was trying to introduce other people to it, because if it was the key to me, it was the key to anybody.”

Loquacious fellow that he is, he started talking to people about the Yoga, and though he felt like he really knew nothing, he would say things he didn’t know he knew. It just came out.

Pondicherry

Loquacious fellow that he is, he started talking to people about the Yoga, and though he felt like he really knew nothing, he would say things he didn’t know he knew. It just came out. Eventually all this led to a now well-known incident in Pondicherry. It was two days after darshan and he was in the Indian Coffee House when he got into a conversation with a burly, Anglo-Indian ex-prizefighter named Malcolm. When Malcolm expressed doubts about the Mother and said openly that she was a fraud, Mickey decided to stay with him to find out why he thought that way.

Finally, late that night, Malcolm blurted out that the woman he had seen on the balcony two days ago was a beautiful young woman—he’d be happy to go out with her—why were there photos of an old woman all over town? Mickey told him that he had probably seen her in her subtle body. Malcolm was thunderstruck.

The next day Mickey took Malcolm to M.P. Pandit, who arranged a darshan with the Mother. But Malcolm had had a dream in which Sri Aurobindo told him not to see her because it might be too much for him at this time, the same thing M.P. Pandit told him when he went to the Ashram. “Since you have seen her subtle body, you can see her anytime.”

“When I came back from the Ashram I had no more doubts,” says Mickey. “They know everything—everything!”

Mickey’s Interview with Clifford

Clifford: Do you remember in the beginning, you used to make an analogy between evolution and us trying to make some kind of progress, and you used to say to be patient. You said, “Just think how long … it took billions of years for the first life form to evolve.”

Mickey: I don’t even remember what I used to tell people. [laughs]

C: Well, you used to say that it took billions and billions of years for the first cells to appear on earth, and then it took so long for life to evolve—so don’t worry about your own progress because it already took you so long to get here.

M: It’s true.

C: I was curious when you said be patient. What scale did you think of? Did you mean be patient within one lifetime, or …

M: I don’t really know, but I tell you, I just picked up a book edited by Dr. [Madhusudan] Reddy because he was here [in the USA]. In it Sri Aurobindo answered somebody’s letter. He said, “The difference between knowledge and faith is that I know the supermind is going to manifest in the earth consciousness. I know that we are going to effectuate a breakthrough. It’s inevitable. I can’t fix the timetable, but I have faith that the period is now.” So, you know, I don’t know these things as an actual fact, but I have faith in what he says. [laughs] I have faith in his faith.

C: What are you hoping for now?

M: Well, to see the supermind, the supramental consciousness, manifest in the whole earth. That’s all.

C: What do you hope for yourself?

M: Just that I can be, some time or other become, a very effective and efficient instrument through which she [the Mother] can work. I don’t have any more personal ambition, because I know an awful lot about my own defects, falseness … who knows it better than the person themself? I’m a long way from—and I’m 67 years old, I might not have a lot of time left. I might, I don’t know … I tell you, at least in my case, boy, there’s so much resistance just against simple things. You know, it must have taken me 20 years to quit smoking cigarettes and grass. You know, maybe 20 years for just that. Pheew! And I didn’t want either one of them. I just used to do it; it seemed to be something mechanical. You know how many years I tried to get through one day without a cigarette? And I would break down all the time. But one day I said, “That’s it.” And do you want to know something? I never had a problem with it. I never had a problem from the minute I said “no more” this time. It never happened again. I don’t get any yens for cigarettes and grass, I couldn’t. But it took years just for those two little simple things that most people—that most people could put down like that.

C: Cigarettes … most people can’t put them down at all.

M: Well, cigarettes are rough on a lot of people. But every time somebody puts down cigarettes, it makes it easier for everybody else to put it down. And that’s a stronger reason than to quit for yourself. And, ah, that goes for a lot of other imperfections and impurities in us. But that’s such a grace to put those things down, because you know, at 67—and I was a heavy smoker—how many years could I go?

C: When you’re feeling bad, depressed, or doubtful, do you have something particular that helps you to get through?

M: The Mother. Yeah, the Mother. I think of the Mother. That doesn’t really happen to me anymore, or if it does, it’s so slight … you know Sri Aurobindo talks about doubts, I think in The Synthesis. Sometimes you get doubts, and the whole edifice that you’ve constructed, the whole construction that you have—of what existence is about—it all collapses with those doubts. But Sri Aurobindo explains that one of the reasons is that if you never had doubts, you’d stay right with that construction, that narrow view. And so the doubts destroy it and only make room for a larger knowledge to penetrate. And I’ve seen this happen in myself so many times that I just know that that’s how it is and so even when … but I never have any doubts about it. Not anymore.

I mean you can see it in everything. It’s like Sri Aurobindo says, you can’t fix a time on it. He also said that even if it was going to be far off in the distant future, there’s nothing else really to do. And even if I had doubts about myself, I know that it’s an inevitability. There couldn’t be any other way.

C: Okay, maybe you don’t care, but are you making progress?

In a subtle way. I seem to have an understanding of a lot of things in a way that I never did before. And this is only in the last couple of years—two or three years. And … I can’t see the Divine in everything, or the divine hand in all actions, but I know that it’s there.

M: I would say, yes. Yeah. In a subtle way. I seem to have an understanding of a lot of things in a way that I never did before. And this is only in the last couple of years—two or three years. And … I can’t see the Divine in everything, or the divine hand in all actions, but I know that it’s there. And when I see things happen that generally people feel bad about, I don’t. I don’t feel bad when I see so-called truth getting a defeat, and I don’t feel elated when I see something very… conducive to growth, to the world, happen. I know that it’s inevitable. There’s no way that it can miss.

When I told you that I used to look for a flaw—I’d say, if I find one flaw in here, then the whole thing isn’t right—it’s all out of kilter, and then the world really is doomed if these two people [Sri Aurobindo and the Mother] are not right because … if they didn’t see it right, who’s going to see it right? They are it. And I never found a flaw; I found a lot of things I don’t understand.

But in my own consciousness, there hasn’t been a doubt about what’s gong to be in this yoga for many years, that it’s going to happen. How it will happen, what form—I don’t know. But I know that a divine life on this earth is just as sure as that this bench is here. And I’ve known that for a long, long time. Sometimes I wish that I could be a pure, a more perfect and more transformed instrument with which to do this work. I see some people are so effective in it, you know. But there’s a tremendous amount of resistance in everybody, and it just has to be overcome.

As to the question about whether there was anything irrevocable that happened in the sadhana [yogic practice]: the feeling or knowledge that the supramental will manifest on earth, and the knowledge that there is nothing else to do with one’s will and action but to consciously try to unify them with the Divine Will—that feeling and knowledge is, I feel, irrevocable.

CLIFFORD GIBSON was introduced to Integral Yoga in Boston by Mickey Finn and edited the book Sunil: The Mother’s Musician.

JOHN SCHLORHOLTZ has taught yoga for older adults and people with disabilities and illness and is the creator of the Ageless Yoga DVD series.