Collaboration Journal

Special Feature

The Wide-Ranging Impact of Maestro Shankar

PHILIP GOLDBERG

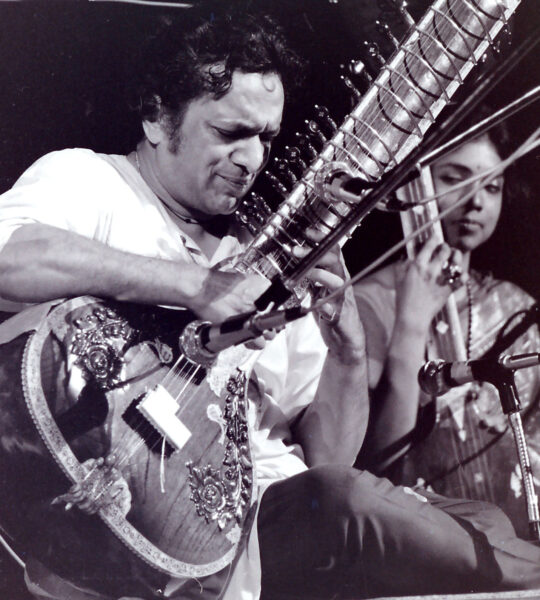

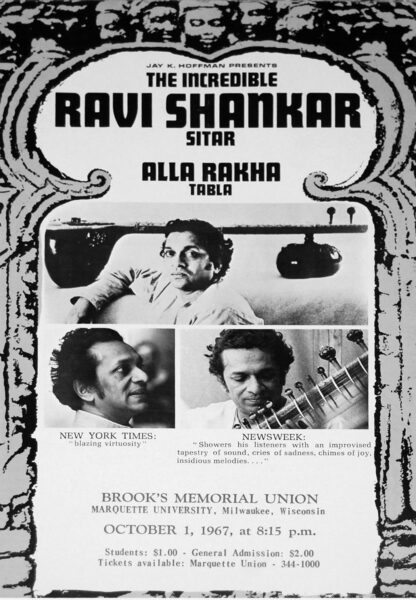

Among the many streams that carried India’s spiritual treasures throughout Western society, one of the most influential was the arts. Among the arts, perhaps the most significant transmission came through music. And in the world of music, the artist with the most far-reaching impact—the influencer of influencers, so to speak—was the great sitarist and composer Ravi Shankar.

Most accounts of Maestro Shankar’s contributions begin with his first concert tour in the West, in 1956. That was, indeed, the start of something big, initially in classical music, then in jazz, then in pop and rock and what came to be called World Music—and, most important for our purposes, the spiritual meeting of East and West. But the antecedents ought to be mentioned. For one thing, Shankar actually came to America in the 1930s, as a teenaged sitarist accompanying the performers in his brother Uday’s dance company, which toured the U.S. to great acclaim.

His music was also appreciated by aficionados of foreign cinema, beginning in 1955 when the first installment of Satyajit Ray’s celebrated Apu Trilogy was released. That trio of films, with their indelible black and white images of Bengal and Benares (now Varanasi), mesmerized audiences, instilling in many an attraction to India, and the effect was magnified by Ravi Shankar’s masterful, understated musical score. I remember seeing Ray’s masterpiece as a student in the late 1960s and having this thought about what I saw onscreen: “Wherever that is, I want to go there.” I also wondered what possible instruments were making the intoxicating, irresistible sounds I heard and hoping I would hear them again.

Classical West Meets Classical East

Shankar’s 1956 American tour was a direct result of his encounter, four years earlier, with the great classical violinist Yehudi Menuhin. The pair met in India, where Menuhin was performing a series of concerts at the behest of the Indian government. “From the moment we met, we clicked, both as musicians and as human beings,” Shankar later recalled. “It was the beginning of not only a very great friendship but a learning and sharing of each other’s work.” As we’ll see, Shankar would soon develop similar relationships with musicians whose platforms were far bigger.

For his part, Menuhin wrote in his autobiography, Unfinished Journey, that Indian music took him by surprise. “I knew neither its nature nor its richness,” he said, “but here, if anywhere, I found vindication of my conviction that India was the original source.” He didn’t just mean the source of good music.

The violinist returned to India several times, and a high point of those trips, he said, was meeting and performing with Shankar. Eventually, he arranged for Shankar, then 36, to perform in the West. He played mainly for classical music fans in recital halls and, occasionally in larger venues such as the prestigious Bath Festival in Great Britain, where he and Menuhin headlined together. The enthusiastic response, although muted compared to the roar that would soon come, led to other collaborations between the two. Their groundbreaking album West Meets East stunned music lovers with its exotic virtuosity and won a Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance in 1967. It was the first Grammy ever awarded to an Asian musician. (The album had two sequels as well.)

It should be noted that Menuhin’s trips to India resulted in a friendship with another luminary he would introduce to the West: the hatha yoga master B.K.S. Iyengar. Menuhin credited yoga with helping him as a musician, calling Iyengar his “best violin teacher.” But he understood that the tradition went beyond the physical and was “primarily a yardstick to inner peace.” Similarly, his reverence for Indian classical music, he made clear to the public, went beyond its esthetic appeal. Its higher purpose, he wrote, is “to make one sensitive to the infinite within one, to unite one’s breath with the breath of space, one’s vibrations with the vibrations of the cosmos.”

A younger star in the classical music galaxy also picked up on those vibrations. In his mid-20s, the innovative composer Philip Glass was hired by a filmmaker named Conrad Rooks to assist Ravi Shankar on the score of a strange avant-garde film called Chappaqua. This was in Paris in late 1965 and early 1966, and at the time Glass had never heard Indian music. Under the tutelage of master Shankar, he became hooked, later saying that the discovery “pushed me towards a whole new way of thinking about music.” Soon, he would be inspired to combine what he learned as a music student with what he picked up from Shankar.

“I got a master’s degree from Juilliard,” he said, “but I felt there were things about music that I didn’t understand. I hadn’t really arrived at a personal language, which happened very soon after that because, at the same time, I had the very good luck of being hired by Ravi Shankar to be his assistant.” The result is reflected in Glass’s distinctive style of minimalism with a generous use of repetition.

Like Menuhin, Glass appreciated the spiritual roots of classic ragas. He traveled in India, became a dedicated Buddhist practitioner (and student of the Dalai Lama), and later based two of his major works on Indic themes. One was the opera Satyagraha, which is based on Mahatma Gandhi’s years in South Africa and employs verses from the Bhagavad Gita. The other was The Passion of Ramakrishna, a concert piece for orchestra and voices based on the last months of the revered master’s life.

More than three decades after they met in Paris, Glass and Shankar, now world-renowned artists, collaborated on a studio album called Passages. Released in 1990, the recording consists of arrangements by each on themes composed by the other. Described on Wikipedia as “a hybrid of Hindustani classical music and Glass’ distinct American minimal contemporary classical style,” Passages reached the number three spot on Billboard’s World Music chart.

All That Jazz

As Ravi Shankar, and Indian music in general, became better known across broader (and decidedly hipper) segments of society, more and more listeners felt the spiritual vibrations Yehudi Menuhin referred to. Why wouldn’t they? The sounds and structures of the traditional raga form was designed to evoke the kinds of spiritual experience that all sacred music aims to induce, only in this case rooted in a systematic understanding of the effects of sound. As a result, many Westerners found it perfectly natural to move from an intense musical experience to a transformative exploration of Indian spiritual teachings.

This was especially true at the next stop of Ravi Shankar’s march through Western musical genres. The spontaneous, in-the-moment creative energy of improvisation that is central to both jazz and Indian classic music is, at its best, ecstatic, ego-transcending, and consciousness-expanding. Musicians and listeners alike recognized this, and over the years jazz artists experimented with Indian motifs and instrumentation while Indian musicians incorporated jazz forms and Western instruments into their repertoire.

The marriage began in earnest in the early 1960s, catalyzed by a little-known and underappreciated music producer in Los Angeles. His name was Richard Bock, and he ran a small music label called World Pacific Records. Bock was what we now call an early adopter. He took up Transcendental Meditation years before the Beatles planted the technique and its principal proponent, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, into the forefront of global attention. Bock also became enamored of Indian music and Ravi Shankar’s genius long before the masses tuned in. He produced some of Shankar’s most successful albums. He also turned leading jazz artists on to his discovery, and some of them would later perform on Shankar’s records.

Chief among the connections Bock made was the fateful one between the sitarist and seminal saxophonist John Coltrane and his wife, the pianist and harpist Alice Coltrane. The resulting friendship would become so deep that the couple named one of their sons Ravi (Ravi Coltrane became a successful jazz musician in his own right).

At the time of their meeting, John Coltrane was already a legendary talent who had played with the likes of Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk and had led his own ensembles. Like other jazz artists of his time, he’d gone through a harrowing period of drug addiction that might have destroyed his career if not his life. However, in 1957, he decided to kick the habit cold turkey. During the intense withdrawal he had what he described as a life-changing spiritual experience. The breakthrough initiated a search for spiritual wisdom and consistent means of transcendence. The subsequent journey took him beyond his Christian heritage and into Islam, Zen Buddhism, Kabbalah, and Hinduism. He read, among other sources, the Bhagavad Gita, books on Vedanta and about Sri Ramakrishna, and works by Jiddu Krishnamurti and Paramahansa Yogananda (principally Autobiography of a Yogi). He also adopted a regular meditation practice.

His diligent seeking extended to new musical forms as well. The introduction to Ravi Shankar was fortuitous. In his memoir, Raga Mala, Shankar wrote that Coltrane was eager to learn how Indian musicians “create such peace, tranquility, and spirituality in our music.” The pair met five or six times, and Coltrane apparently soaked up what the maestro spilled out. They planned to carve out six full weeks of dedicated study, but it wasn’t to be. John Coltrane died of liver cancer at the age of 40 on July 17, 1967. He’d kicked heroin ten years earlier, but apparently the damage had been done.

Before his tragic death, however, Coltrane left an indelible mark on America’s cultural and spiritual landscape. And that influence was shaped in large part by Indian music and Indian spirituality. He once stated his spiritual convictions in Vedantic terms that would have pleased the likes of Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo: “I believe in all religions. The truth itself has no name on it to me, and each man has to find it for himself.” His musical mission was shaped by that perspective: “I’d like to point out to people the divine in a musical language that transcends words.”

That intent—that sankalpa if you will—was shaped in large part by the infusion of Indian motifs into his musical repertoire and yogic insights into his spiritual repertoire. The titles of some of his songs and albums reflect that: “India” (on a live album called Impressions), Ascension, Meditations, and Selflessness, not to mention Om, a 28-minute song recorded in 1965 and released posthumously. Coltrane described om as “the first vibration—that sound, that spirit, which set everything else into being. It is the word from which all men and everything else comes, including all possible sounds that man can make vocally. It is the first syllable, the primal word, the word of power.”

Anyone who hears Om—the Coltrane recording, not the primordial sound itself—is likely to retain memories of it, either in agony or ecstasy. It begins softly enough, with quiet percussion. Then the musicians chant, in English, chapter 9, verses 16 and 17, of the Gita:

Rites that the Vedas ordain, and the rituals taught by the scriptures, all these am I, and the offering made to the ghosts of the fathers, herbs of healing and food. The mantram. The clarified butter. I, the oblation and I, the flame into which it is offered. I am the sire of the world, and this world’s mother and grandsire. I am he who awards to each the fruit of his action. I make all things clean. I am Om!

And with that, Coltrane and his band chant “Om”—not the way it’s chanted in yoga studios and satsangs, but more like a scream, “as if they are caught on fire by it,” in the words of one music critic. The music that follows the chanting is, for the most part, wild, raucous, and to many ears, as clamorous as a Manhattan construction site. In fact, many of Coltrane’s later recordings have a harsh, discordant quality. This comes as a surprise to people who expect soothing “spiritual” music from such an authentically spiritual artist. In an insightful article aptly titled “Trane of No-Thought” in the Buddhist magazine Lion’s Roar, Sean Murphy explains it this way: “These works were intended by Coltrane as 100% spiritual testament, the communication of an ongoing, endless spiritual quest into the great mystery, rather than any kind of peaceful and harmonious arrival at answers.”

That strikes me as correct. Coltrane’s spiritual music expresses the restless energy, and sometimes frustration, of a determined seeker, not the serenity of someone who thinks he’s found the answers. One feels the aching pain of separation from the Divine and the longing to mend that separation in the oneness of yogic unity.

The ultimate expression of Coltrane’s East-turning spirituality is his breathtaking 1965 album, A Love Supreme. A moving blend of spiritual moods in four movements—”Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm”—the masterpiece is the second highest selling jazz album of all time (the first is Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, on which Coltrane plays tenor sax). The album, by the way, is heard in every Sunday service at the Saint John Coltrane Church in San Francisco.

Musicologists have pinpointed the influence of Indian music on Coltrane’s later work, including his classic take on Rogers and Hammerstein’s “My Favorite Things.” Readers can easily track those analyses down. Here we’re more concerned with India’s impact on Coltrane’s spiritual quest, and that was profound and unmistakable. “Once you become aware of this force for unity in life, you can’t forget it,” he wrote in 1965. “It becomes part of everything you do … my goal in meditating on this through music however remains … to uplift people as much as I can. To inspire them to realize more and more their capacities for living meaningful lives.”

The same aspiration was shared by his wife, and she lived long enough to pursue it fully. A gifted musician in her own right, Alice Coltrane continued the couple’s legacy to unusual heights. She became a close student of Swami Satchidananda, the founder of the Integral Yoga Institute who was known as the Woodstock Guru after he opened the famed festival with a talk and a chant. Later, she became a devotee of Sathya Sai Baba, delved into the Krishna bhakti tradition, and dedicated herself to the sannyasi life. As Swamini Turiyasangitananda, she founded the Shanti Anantam Ashram in the hills outside Los Angeles in 1983, where she served as spiritual director until her passing in 2007. It should come as no surprise that her satsangs featured devotional music with elements of blues, gospel, jazz, raga, and kirtan. She also recorded several albums, with song titles reflecting her spiritual orientation, e.g, “Journey in Satchidananda,” “Rama Rama,” “Sivaya,” “Jai Ramachandra,” “Radhe Shyam,” “Govinda Jai Jai.” The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda, produced after her passing, is a compilation of music recorded during satsangs at her ashram.

The reach of Indian music and spirituality into jazz extended far beyond the Coltranes and is too complex to detail here. But one other artist warrants mention. In the early sixties, Paul Horn was a highly regarded flautist in the LA club and recording scene (he also played sax and clarinet). Horn knew Richard Bock, who apparently knew everyone. Bock introduced Horn to Ravi Shankar and to Transcendental Meditation, and the musician took to both the person and the practice. He adapted his flute to the nuances of Indian ragas to play on Shankar’s mesmerizing album, Portrait of a Genius. Later, he journeyed to India and the Rishikesh ashram that would soon be made famous by the Beatles, becoming one of the earliest Americans certified as TM teachers. Soon after, when (as we’ll see) demand for TM exploded, he left the music scene to travel around the U.S. teaching.

While in India, he made the obligatory side trip to the Taj Mahal, where his musician’s ear was drawn to the extraordinary acoustics in the inner chamber. He returned to India in 1968 to join the Beatles and other musical celebrities at the Maharishi’s ashram, and while in the country teamed up with Indian artists provided by Shankar on two albums, Paul Horn in Kashmir—Cosmic Consciousness and Paul Horn in India—Ragas for Flute, Veena, and Violin. Of greater historic significance, he also returned to the Taj Mahal, only this time with his flute and a tape recorder. He didn’t plan on his improvisations becoming an actual record album, but that’s what happened. Inside, released in 1969, was groundbreaking and career-changing. Horn went on to record albums inside other sacred sites with good acoustics, including Egypt’s Great Pyramid, earning a sobriquet that seemed to both amuse and annoy him: Father of New Age Music.

To be fair, another celebrated jazz musician of Horn’s vintage was also called the Father of New Age Music. Clarinetist Tony Scott, who had played with the likes of Billie Holiday, was another seeker who turned to the East. In a lengthy sojourn in Japan, he recorded the sublime Music for Zen Meditation with traditional Japanese musicians, then followed it, after a pilgrimage to India, with Music for Yoga Meditation. The song titles on that record suggest they were named by a knowledgeable yogi: “Prahna (Life Force),” “Shiva (The Third Eye),” “Samadhi (Ultimate Bliss),” “Hare Krishna (Hail Krishna),” “Hatha (Sun and Moon),” “Kundalina (Serpent Power),” “Sahasrara (Highest Chakra),” “Triveni (Sacred Knot),” “Shanti (Peace),” and “Homage to Lord Krishna.”

Here Comes the Sun

The opening sentences of Chapter One in my 2010 book, American Veda, are: “In February 1968 the Beatles went to India for an extended stay with their new guru, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. It may have been the most momentous spiritual retreat since Jesus spent those forty days in the wilderness.”

I expected blowback. I thought some people would be offended and others would argue that I was wrong. I never heard a word.

I take that as evidence of the Beatles’ monumental impact on the spiritual meeting of East and West. The phenomenon has been analyzed and memorialized countless times by journalists, historians, musicologists, filmmakers, and cultural commentators, so there is no need to rehash the details here. What should be noted is that, once again, Ravi Shankar played a pivotal role.

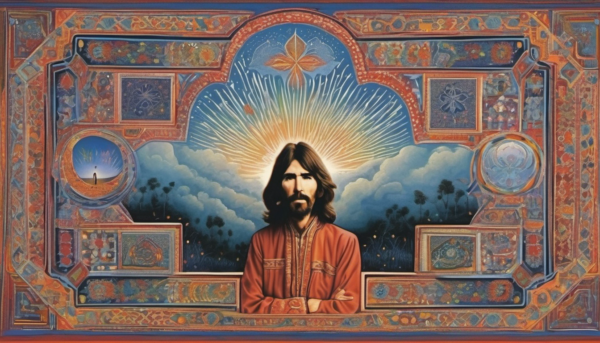

Yehudi Menuhin, Philip Glass, and John Coltrane are towering figures in the history of Western culture, and the significance of their encounters with Shankar is enormous. But for sheer planetary impact, those friendships were dwarfed by the seismic eruption that followed the meeting of Shankar and George Harrison.

The seed was planted in April, 1965, in an Indian restaurant serving as a set for the Beatles’ movie Help! That’s when George first heard the sound of a sitar. A few months later, he bought one in a London shop. He learned some rudimentary licks and played the instrument in the opening bars of “Norwegian Wood,” on the Rubber Soul album. Harrison also used Indian instruments and Indian musicians on “Love You Too” and “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the apex—or the nadir depending on your perspective—of the Beatles’ psychedelic phase.

In short order, the hypnotic sound of the sitar came to define the psychedelic subculture of the sixties, much as the tenor sax had come to define jazz. So many pop musicians employed Indian sounds that a mini-genre called raga rock was born. Among those who got in on the act were the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead, the Byrds, the Incredible String Band, the Yardbirds, Procol Harum, The Animals, and Jethro Tull (in later years, Tom Petty, Stevie Wonder, Elton John, Green Day, Alanis Morissette, and Red Hot Chili Peppers, among others, would follow suit).

George didn’t like it. Never one to suffer fools gladly, he told the press that he was “fed up with the way the sitar has become just another bandwagon gimmick with everybody leaping aboard it just to be ‘in.’” He added, “A lot of people will probably be saying that I’m to blame anyway for making the sitar commercial and popular, but I’m sick and tired of the whole thing now, because I really started doing it because I want to learn the music properly and take it seriously.”

To fulfill that desire he needed a teacher, and if you’re one of wealthiest, most famous people in the world, you can get a world-class one. Re-enter the great connector, Richard Bock. The producer had turned David Crosby, then member of the Byrds, onto Ravi Shankar, and Crosby shared the discovery—in an LA hot tub, reportedly—with George. The rest is musical and spiritual history.

Harrison met Shankar in London in mid-1966, and a few months later was off to India to study sitar with the master. By then, having abandoned the Catholicism he was raised in, having had a taste of transcendence through psychedelics, and having grown tired of the hippie drug scene, he was searching for answers to the big questions about human existence and our place in the cosmos. That made him receptive to the spiritual underpinnings of the music he was drawn to. Among other grist for his mill, he was given books to read, and by his own account, at least two of them would have a lasting impact: Swami Vivekananda’s Raja Yoga and Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi, a stack of which he kept around for gift-giving.

Harrison returned to London, more skilled at the sitar, far more knowledgeable about core Vedantic teachings, and ripe for more of both. And, to his own astonishment, Ravi Shankar had big changes in store for him as well. The pop stars who dabbled in the sitar may have been derided as amateurish trend-followers, but the instrument’s sudden popularity called attention to a genuine virtuoso with deep spiritual roots and the cachet of being mentor to a Beatle. As a result, Shankar’s record sales took off and he performed sold-out concerts in larger and larger venues. The new stardom was cemented with a triumph at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and his performance there provided the climax of the concert movie Monterey Pop. All of this helped move thousands of young people to explore the spiritual tradition that had birthed the music they experienced as simultaneously serene, exuberantly free, and transcendent.

For counterculture consciousness-expanders especially, being at a Ravi Shankar concert was euphoric, not just because they were discovering a sublime musical form, but because they could sense that, for the artists performing it, the music was holy. You could see it in their eyes, and in their repose, and in the way they approached the stage as if it were a sanctum sanctorum. And the music itself evoked the cosmic order, with a changeless drone anchoring a raging, unpredictable dynamism. At the very least, listeners realized that a culture they’d thought of as backward was capable of producing sublime and sophisticated art. And if that were true of its music, why wouldn’t it also be true of its spiritual tradition?

In June of 1967, the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Among the panoply of cultural figures on the iconic cover, four were selected by George: Yogananda and the three gurus in his parampara. As was typical for the Fab Four, only one of George’s songs was on that album, but it was a shape-shifting selection. I’ve called “Within You Without You” the first rock and roll Upanishad. Check out the lyrics and listen to the skillful blend of Indian and Western musical motifs.

By now, George was a serious seeker, eager for some kind of initiation. When, in August, his then-wife Pattie Boyd heard that Maharishi Mahesh Yogi was going to be speaking about meditation at the London Hilton, she gathered her husband and his mates and off they went. They met with the guru backstage, and a few days later, along with their wives and a few friends like Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull, they boarded a train to Wales, where they would learn to meditate. The resulting media frenzy—amplified the following February when the lads and other celebrities (Donovan, Mia Farrow) took off for their watershed meditation retreat in the Himalayan foothills—was so monumental it was as if the earth had tilted on its axis, allowing ancient wisdom to flow more quickly and smoothly from East to West.

It was the beginning of the mainstreaming of Indic spiritual precepts, meditation, and the rest of the yogic repertoire. After all, if you were promoting anything in those days, even something previously reserved for weirdos, what better spokespersons than the lads from Liverpool? They even supplemented their public advocacy in songs like “Fool on the Hill” and “Across the Universe.”

In time, of course, the media moved on to other trends and the Beatles settled into the studio for their final recordings as a group. But for George Harrison, what started as an attraction to the sound of the sitar continued as a spiritual mission. No artist has ever embraced India’s spiritual treasures more intimately or promoted it more fervently.

He seems to have embraced a range of yogic pathways, keeping up his meditation practice and lifelong study, becoming a bhakta with an enduring association with the Krishna Consciousness lineage, and doing his share of karma yoga—most memorably teaming up with Ravi Shankar for the Concert for Bangladesh, the landmark fundraiser in Madison Square Garden that was also made into a documentary film and a Grammy-winning album.

Musically, much of his post-Beatle output featured dharmic precepts and Indian motifs—not just as a composer, lyricist, and singer, but in his role as a producer as well. In 1971, he produced (and played on) an album titled The Radha Krsna Temple, consisting of kirtan performed by Hare Krishna devotees and featuring a rocking version of the Krishna mahamantra that, astonishingly, became a top-ten single.

From All Things Must Pass in 1971 to the posthumously released Brainwashed in 2002, one can extract lyrics that, taken together, might constitute a primer on yoga and Hinduism. Right from the start, on “My Sweet Lord,” perhaps the most loved of George’s songs, he voices the yearning of a God-seeker: “I really want to know you,” he cries. As he intones variations on “my sweet Lord,” the chorus sings “Hallelujah,” then “Hare Krishna,” then the traditional invocation “Guru Brahma, Guru Vishnu, Guru Devo Maheswara.” The mix was purposeful. Harrison said he wanted to show that Christian and Hindu sounds of praise “are quite the same thing.”

On “Beware of Darkness,” he warns seekers about worldly distractions, e.g., “falling swingers” and “thoughts that linger.” On “Awaiting on You All,” he tells us to chant the names of the Lord if we want to be free. On “The Art of Dying,” he counsels us to transcend bodily identity and to know that most of us will, in time, return to earthly incarnations.

In the 1973 album, Living in the Material World, Harrison voices the challenge of pursuing enlightenment in the worldly realm. The song titles include “The Lord Loves the One (That Loves the Lord),” “The Light That Has Lighted the World,” “Be Here Now,” and “Give Me Love,” a foot-stomping howl of spiritual yearning:

George Harrison died in November, 2001. The title song on his final album, Brainwashed, was completed after his passing by his son, Dhani (named for the notes dha and ni in Indian music) and friends. It can be seen as his spiritual valedictory. In it, he calls out fiercely the many ways maya deceives us in the modern world and offers a calming Vedantic antidote. Calling God “the wisdom that we seek,” he evokes the classic attributes of the Divine: sat chit ananda (existence, consciousness, bliss). He quotes a passage from the Yoga Sutras and closes with a haunting Sanskrit invocation to Shiva and to Parvati, the embodiment of the Divine Mother.

Fittingly, just before receiving his cancer diagnosis, Harrison managed to produce one final collaboration with his great teacher and friend. Chants of India, released in 1997, was a Ravi Shankar tour de force and a labor of love by both men. It contains prayers and chants from the Rig Veda, the Upanishads, the Gita, and other sources, as well as original Shankar compositions, which he said he tuned “in the same spirit” as the traditional slokas and mantras.

Shankar, who died at age 92 in 2012, a month after his final performance, once recalled that Harrison, after hearing playback from the Chants sessions, “embraced me with tears in his eyes and simply said, ‘Thank you, Ravi, for this music.’”

We should all thank him.

PHILIP GOLDBERG is a popular public speaker, workshop leader, and author of the award-winning American Veda: From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation.